Page 2: Assembling the Chassis

Since I have already written about the build of the original TRF 414X

chassis in great detail, I am going to concentrate on the differences

when writing about the TRF 414M here. Please see my TRF 414X page for more details on the original.

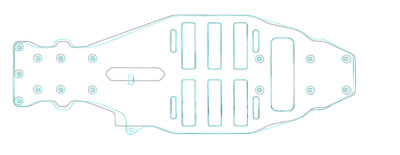

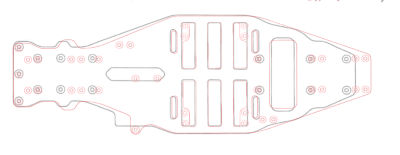

I prepared these images comparing the TRF 414X chassis plate (black)

to the TRF 414 version (blue) and the TRF 414M version (red) using

extractions from the manual and overlaying them. You can see that

there are many similarities, but the primary difference is the increased

length on the TRF 414M. You can also see the addition of a

mounting flange so the steering servo can be attached to both updated

chassis. In all cases the 6 rectangular slots are to allow

individual battery cells to sit low and the large rectangular slot in

the rear (right hand side) is for the motor.

While the TRF 414X started by building the differentials and

bulkheads and adds the suspension later, the TRF414M separates the

suspension mounts from the bulkheads so they can be installed

first. This requires many more holes in the chassis plate as can

be seen in the previous chassis comparison images. The images

above show the installation of the inner aluminum suspension mounts

(they were Nylon on the 414X) and the steering posts.

The TRF 414X suspension arms were machined from blocks of Nylon, but here we have carbon fiber filled molded arms which are much stiffer. The hinge pins of the 414X just slipped through holes in the suspension mounts, but here there are ball joints on the ends of the hinge pins which fit into machined pockets in the mounts. The anti-squat angle (incline of the hinge pin) can be adjusted by adding or removing spacers under the suspension mounts differentially. By default the front mount uses 0.7mm spacers and the rear mount uses none resulting in a slight incline. The roll center can be adjusted by adding or removing spacers under the suspension mounts symmetrically. The toe angle of the rear suspension is fixed by the geometry of the uprights at 2° using identical front and rear suspension mounts, but can be modified to 2.5° by changing to a slightly wider rear mount. Ground clearance can be adjusted by turning the set screw in the front inner corner of the arms which restricts their maximum travel by contacting the chassis plate. In general there is more adjustability here than on the 414X and it is easier to perform changes.

Note that most of the "new" plastic parts including the arms, the

uprights, the knuckles, the hub carriers, and the pulleys are actually

from the TA-04.

Now we can do the same thing for the front suspension. The

assembly is pretty much the same as the rear. There is no front

toe angle in the suspension arms since this is intended to be adjusted

by changing the length of the steering links instead. Note that

small changes in wheelbase can be accommodated by moving the spacers on

the hinge pin. There are 4.7mm of spacers used on both the front

and the rear with the arms biased toward the rear by default in both

cases. The kick-up angle of the front arms is the same as the rear

using 0.7mm spacers under the front suspension mount.

Time to build the rear ball differential. The pulley has the

same number of teeth (32) and uses the same number (10) and size (3mm)

of balls as that of the TRF 414X, but now the pulley is molded plastic

instead of aluminum so it doesn't need Delrin inserts for the

balls. The steel drive cups are machined from smaller diameter

bars by using plastic housings to adapt to the pressure plates.

All of this tends to reduce the rotating mass (but it's not as cool).

The front one-way is built using separate one-way bearing housings

for the left and right axles, as opposed to the TRF 414X which used a

single housing with two one-way bearings in it. While the 414X

used a different pulley for the front one-way, the 414M uses the same

ball diff pulley used in the rear and just bolts the bearing housings to

it as shown.

The rear machined bulkheads look quite different than those used on

the TRF 414X. The overall geometry is the same and the bearings

are still pressed into the bulkheads from the factory, but now the motor

mount has been removed into a separate part and the suspension blocks

are no longer mounted directly to the bulkheads. This results in

bulkheads which look a lot thinner and less substantial than

before. The motor, center pulley, and rear axle all end up in the

same place though. The lateral stiffener has also has some cooling

fins added. They probably don't do anything, but they look

important.

Here is the completed rear bulkhead assembly both before and after

being installed onto the chassis. One subtle difference is that

adjustability of the motor position for

pinion mesh was vertical on the 414X and is now horizontal on the

414M.

This is why the motor clearance slot in the chassis plate had to be

made a bit wider. Note how the suspension mounts are now

completely independent from the bulkhead allowing them to be altered

without removing the driveline. Likewise the ball differential can

be removed for maintenance without disassembling the entire suspension.

The front bulkhead has fewer differences from the TRF 414X than the

rear, but the suspension blocks have still been removed from the

assembly. An exploded view is shown on the left and the installed

assembly on the right.

The TRF 414X did not come with any anti-roll bars, but the 414M comes

with 3 full sets of front and rear bars with different diameters

(red=soft, yellow=medium, blue=hard). These pivot on the bulkheads

and connect to the lower suspension arms with ball joints.

Unfortunately I found that because of the amount of play in the bulkhead

pivots, the bars are not really effective at communicating suspension

position between left and right sides. Later generations of TRF

chassis would fix this problem by adding set screws to the pivot

brackets allowing the builder to adjust for a snug fit.

The TRF 414X used CVD style drive shafts which were pre-assembled,

but here we have individual components retained by set screws instead of

press fit of the pins. Much easier maintenance this way.

The biggest obvious difference is that the new rear uprights are now

carbon reinforced plastic parts instead of aluminum, but with the same

basic geometry. There are now two hole options for attaching the

camber link instead of one. The same narrow hexes with o-ring pin

retainers are used. If you look closely at the right hand image

you can see the 2° toe angle label molded right into the upright body.

Here I've assembled the rear uprights with their bearings and

axles. On the right I've completed the rear suspension by

installing the axles and camber links. The anti-sway bar just fits

in the space between the rotating axle and the upper link.

Like the rear suspension, the biggest change in the front suspension

from the TRF 414X is replacing the aluminum hub carriers and knuckles

with plastic parts. This does much to reduce the unsprung weight

without sacrificing too much strength. The lower kingpin now gets a

sleeve to rotate on while the upper kingpin gets an integral ball joint

instead of having the ball at a separate location which results in a

higher upper suspension link.

The complex looking steering assemblies are shown completed at the

left. These are pinned into the lower arms and then the front

suspension is completed by adding the upper camber links as shown.

The attachment of the anti-sway bars is somewhat different than in the

rear.

The steering bellcranks (aluminum) and bridge (carbon fiber) appear

to be the same parts from the TRF 414X, but the rod ends are now the

closed ball type with smaller 5mm balls. The assembly has to be

passed between the upper and lower parts of the belt and then slipped

over the steering posts. While the 414X had all 10mm worth of

spacers on top of the cranks, the 414M moves the cranks up by putting

4mm of spacers beneath the cranks and the remaining 6mm on top.

I've actually got this wrong in the picture on the right, an error I

discovered and corrected later.

The upper chassis deck has been modified from the TRF 414X to be a

symmetric design, but is otherwise quite equivalent in shape and

stiffness. A bigger difference is the addition of these plastic

supports to allow the use of a standard 7.2V stick battery pack mounted

laterally. It is still possible to mount individual cells in a

saddle configuration but required that the mounting tabs for the plastic

supports be manually trimmed off the chassis plate. No

thanks. I'll stick with the brackets.

Here's a detail that didn't exist at all on the TRF 414X: radius arms

for the front suspension. Given that the front one-way prevents

any braking forces from being applied to the front wheels, I'm a bit

surprised these were necessary. Still, they certainly result in

much improved longitudinal stiffness. The additional parts shown

on the left are for a new belt support.

From this side view you can see the new ball bearing belt

support. The manual titles this a "tension pulley". While it

does add a bit of tension to the belt, it is not adjustable. It

does provide some support to prevent the belt from "slapping" at high

speed though. The increase in belt height driven by this pulley is

why the steering cranks needed to be raised 4mm.

The shocks have been modified a bit from those on the TRF 414X.

Apart from the obvious difference in color, these new shocks now have a

threaded body which allows the use of a movable spring perch for easy

preload adjustment instead of using spacers. There is also one

fewer o-ring which has been replaced with a rod guide, a urethane

bushing has been added above the bladder, and the number of holes in the

piston has increased from 2 to 3. While the TRF 414X came with 3

sets of springs with different rates, only a single set is included here

which also means the same stiffness has to be used on the front and

rear. These seem equivalent to the stiff rate springs from the

414X. The carbon shock towers are shown on the right. They

share the same overall proportions as those from the 414X but have fewer

holes. Note that the 6 outer lower holes on each tower which were

used for camber link attachment options on the 414X are actually not

used at all on the 414M; the links attach directly to the bulkheads.

Here the shocks and towers have been installed to the front and rear

suspensions on the chassis. The only difference between the

configuration of front and rear is the amount of default preload applied

to the springs (1mm in front, 3mm in rear).

The TRF 414X used a 120T 64p spur gear from Kimbrough. This time they included 3 Tamiya options using metric 0.4mod pitch instead: 112T, 120T, and 128T. This allows a greater variability in available gear ratios because both the pinion tooth count and the spur tooth count can be varied. The massive amount of adjustability varies from a final drive ratio of 4.98:1 (112T spur with 48T pinion) to 10.92:1 (128T spur with 25T pinion). The default configuration uses a middle ratio of 6.40:1 (120T spur with 40T pinion). The 414X used a 35T pinion for comparison so the 414M is geared for more speed out of the box.

Note that 0.4mod = 63.5p so the two pitches are functionally interchangeable, though not technically identical.

I've added a standard silver can motor here just to fill the space. I don't plan to run this model.

The TRF 414X and 414M use the same high torque servo saver, but

whereas the 414X steering servo had to be installed with foam tape, the

414M adds aluminum mounting posts and provisions on the chassis to

attach them. This is a vastly superior system and was one of the

few complaints I had about the 414X.

The body posts and foam bumper are carried over from the TRF 414X,

but the bumper mount has had some strengthening ribs added. The

completed rolling chassis is shown on the right (without a speed

controller, receiver, or battery).

The TRF 414X came with aluminum setting dishes but no wheels or

tires. The 414M flips this around and comes with new 24mm wheels,

tires, and inserts. Everything is installed and completed as shown on the right.